As we're getting closer to the end of the post-production of our first documentary, it feels right to explain how the documentary came to life.

For the first time in human history, we have created a species that possesses everything and enjoys nothing. The average Western human has access to more information than all previous generations combined, yet cannot sit still for five minutes without checking their phone. They own more objects than medieval kings, yet feel perpetually behind. They can connect instantly with anyone on Earth, yet trust no one. This is the fundamental paradox of our age: infinite resources, zero satisfaction.

The symptoms are everywhere. Anxiety disorders have reached epidemic proportions in the most prosperous societies on Earth. Children who have never known hunger experience crippling fear about their futures. Adults with successful careers lie awake at night, scrolling through the lives of strangers, feeling inadequate. We have solved the problem of scarcity and created the crisis of abundance. The question is not whether this is sustainable – it clearly isn't. The question is whether we can still remember another way.

My wife and I moved to Bulgaria in search of something different, authentic, real, something with human connection. After years of building our lives in Sweden, we found ourselves returning to Bulgaria every summer—drawn back by landscapes that challenge every assumption, flavors that tell centuries of history, music traditions that have influenced folk movements across Europe, and most of all, the people whose stories deserved a global audience.

Over time, what started as nostalgia became something clearer—a recognition that we belonged here, building something meaningful from our heritage and contributing to the country's future. We created Това е България out of conviction, not nostalgia.

We started with the idea to create a series of documentaries about Bulgaria, and along the way we met Rory Miller, a former chef who spent three years traveling from village to village learning about disappearing Bulgarian village recipes. I assumed we were documenting the end of an old way of life. What we discovered instead was disturbing: homo sapiens had evolved into something unprecedented – a creature that had optimized for wanting more rather than needing less. In the village of Chelopek, people still measure "na oko" – by the eye, without measuring at all. They may be the last humans who remember what our species lost when it chose infinite choice over infinite time. This is their story. But more importantly, it's a warning about ours.

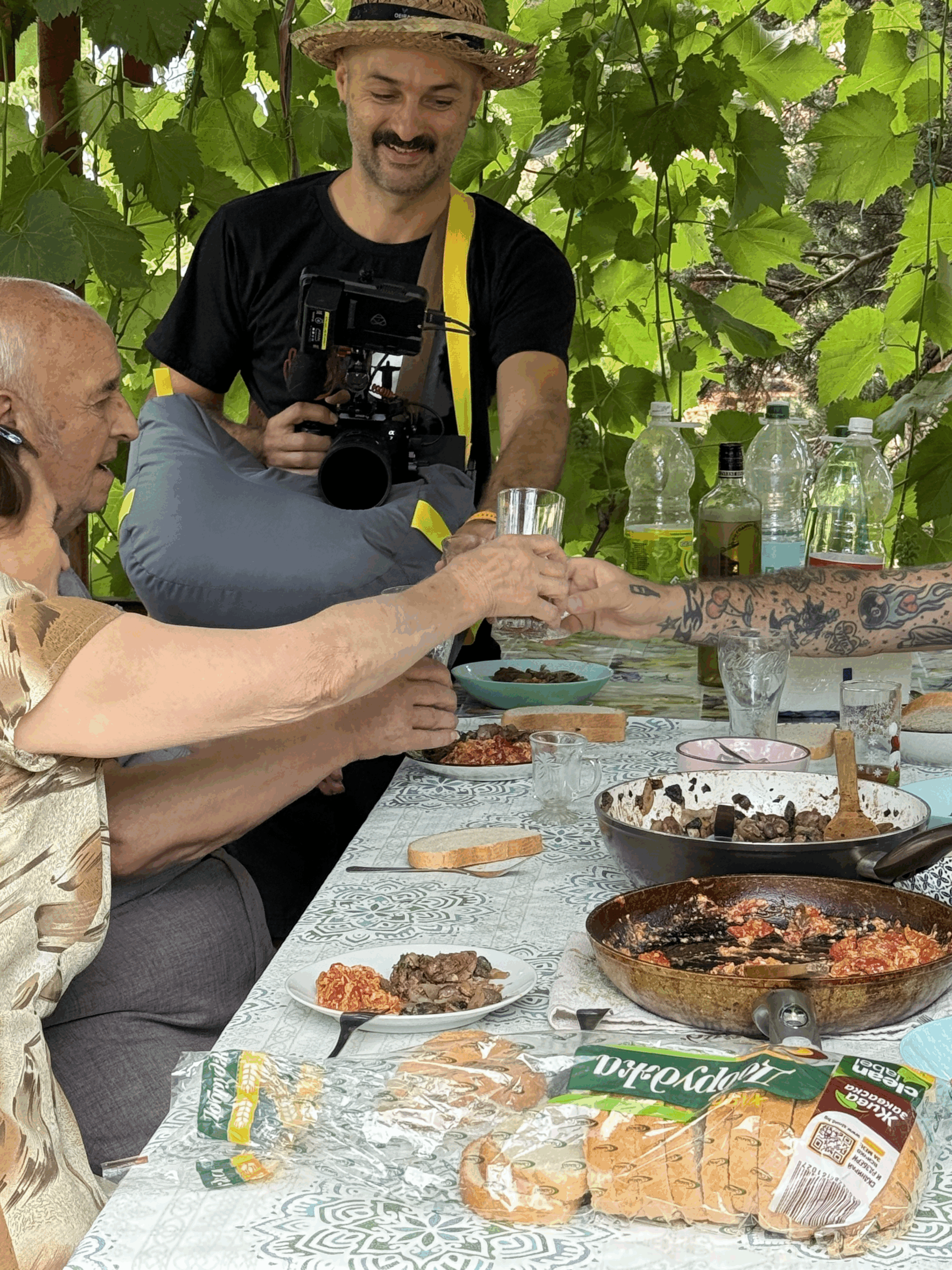

The transformation began the moment I met Baba Tanche and Dyado Vasil. Their faces carried decades of Bulgarian history – wars, communism, the transition to democracy, economic collapses, revivals. Every line etched into their skin told stories of survival that would break most modern humans. Yet these same people, who had every reason to be suspicious, cynical, hardened by experience, greeted our film crew – complete strangers with cameras and questions – as if we were returning family members. No background checks. No small talk designed to assess our intentions. No hesitation. Just "Ela, yazh." Come, eat.

This wasn't politeness. It was something far more radical. In Sofia, in London, in New York, people perform elaborate social dances before trusting someone with their WiFi password. Here were people who had survived Stalin and Hitler, who had seen neighbors disappear in the night, who had lived through the complete collapse and rebuilding of their society multiple times, and they opened their doors to strangers without a second thought. The equation was backwards. Those who had experienced the worst of humanity had retained the most faith in it. Those living in the safest societies in human history trusted no one.

Watching Baba Tanche cook shattered my understanding of efficiency. Her kitchen contained perhaps twenty items total. Five core ingredients – flour, eggs, yogurt, cheese, salt – formed the basis of dozens of dishes. Her hands moved without measuring, adding a pinch here, a handful there, guided by decades of muscle memory passed down through generations. "Na oko," she said when I asked about measurements. By the eye. You know when you know.

Meanwhile, my kitchen contained three different types of vinegar, specialty salts from four continents, gadgets for every conceivable food preparation task, and cookbooks promising restaurant-quality results in thirty minutes. Yet I ate most meals standing at the counter, scrolling through my phone, barely tasting what I'd spent forty-five minutes preparing from a recipe with twenty-seven ingredients. Baba could create a meal that tasted like home itself using ingredients that cost less than my morning coffee. Her efficiency wasn't about doing more things faster. It was about doing fewer things completely.

The mathematics of their daily life defied everything I'd been taught about progress. Dyado Vasil woke with the sun, not an alarm. His day unfolded according to what needed doing – the garden, the animals, conversations with neighbors, repairs around the house. Time moved in circles, not straight lines. There were no calendar notifications, no productivity apps, no optimization. Yet everything that mattered got done. Not eventually. Naturally.

I watched him spend three hours fixing a neighbor's fence, then two more drinking rakia and discussing village politics. In my world, this would be five hours of lost productivity. In his world, this was life happening exactly as it should. The fence got fixed. The relationship got strengthened. The community got maintained. Nothing was optimized. Everything was accomplished.

The children revealed the starkest contrast. The great-grandchildren played with sticks, stones, and imagination. They could entertain themselves for hours with nothing but what they found in the yard. They knew every neighbor, every dog, every tree. They moved through the village like they owned it, because in a way, they did. It was theirs in a way my neighborhood would never be mine.

The weekend in Chelopek forced me to confront an uncomfortable truth: we hadn't solved the right problem. For all of human history, the challenge was scarcity. Not enough food, shelter, security, opportunity. So we built systems to create more. More production, more efficiency, more choice, more growth. We succeeded beyond our wildest dreams. And in succeeding, we created a new form of poverty that no one knows how to solve.

This poverty doesn't look like poverty. It looks like success. It looks like the young professional with the perfect apartment and the growing career who takes medication to sleep and medication to wake. It looks like the family with two cars and three vacations a year who can't sit through dinner without checking their phones. It looks like children with every advantage except the ability to be satisfied with anything for more than five minutes.

Baba and Dyado aren't living in the past. They're living in the present – something we've engineered out of existence. We replaced presence with productivity, satisfaction with stimulation, enough with more. We created a world where having everything means enjoying nothing, where infinite choice leads to decision paralysis, where being connected to everyone means being close to no one.

The most disturbing realization came on my last morning in Chelopek. I'd been there three days. My phone had been off most of that time. I'd eaten every meal without distraction, slept without scrolling, woken without immediately reaching for a screen. I felt a peace I hadn't experienced in years. Not happiness exactly, but something more fundamental. Presence. Groundedness. The absence of that constant, low-grade anxiety that had become so normal I'd stopped noticing it.

Then I turned my phone back on. Hundreds of notifications flooded in. Emails marked urgent that weren't. Messages that expected immediate responses about things that didn't matter. Updates about people I barely knew doing things I didn't care about. Within minutes, that background hum of anxiety returned. My breathing shortened. My mind started racing through to-do lists. I was reconnected to everything and present to nothing.

This is what we've done to ourselves. We've created a species that can no longer tolerate its own existence without constant distraction. We've built a world that demands our attention every waking moment, then wonder why we're exhausted. We've optimized for everything except the only thing that matters: the ability to be here, now, with what we have.

The people of Chelopek aren't special. They're not enlightened. They're not trying to teach anyone anything. They're simply living the way humans lived for thousands of years before we decided that wasn't enough. They measure "na oko" because they know that constantly measuring everything is its own form of blindness. They trust strangers because they understand that a life without trust isn't worth protecting. They have time for everything because they don't try to do everything.

What I documented in Bulgaria wasn't the past. It was a parallel present, one where the trajectory of progress took a different path. Where efficiency meant doing less, not more. Where wealth meant time, not money. Where success meant being satisfied with what you have, not constantly reaching for what you don't.

The title of this film, "This is Bulgaria," isn't meant to romanticize a country or a culture. It's meant to show that another way exists. Not in theory, not in the past, but right now, in places where people still remember that the point of life isn't to optimize it. The point is to live it.

As I write this, I can feel the pull of my phone, the anxiety of unchecked messages, the pressure to be productive. The lessons of Chelopek fade quickly in the face of modern life's demands. But sometimes, when I'm cooking, I put away the measuring cups and try to work "na oko." Sometimes I manage to eat a meal without distraction. Sometimes I remember that the most radical act in a world obsessed with more is to know when you have enough.

The past doesn't reject the future in Chelopek. It embraces it, carefully, selectively, taking what serves life and leaving what doesn't. They have smartphones but don't live in them. They have cars but still walk to visit neighbors. They have access to the world but choose to inhabit their village.

This is what we've forgotten: choice isn't freedom if you can't choose to stop choosing. Progress isn't progress if it makes you less capable. Efficiency isn't efficient if it consumes the very life it was meant to improve. The people of Chelopek know this. They measure by the eye because they understand that not everything needs to be measured. Some things just need to be lived.